"The Boundary Has Long Been Exceeded"

Chemicals in the environment have long been considered minor. Now, for the first time, researchers have defined how many chemicals the earth can handle before the global ecosystem collapses. The finding: chemicals are much more dangerous than long thought. Action is now immediately urgent.

It's news that almost got lost in the daily news: people - or rather, the people of a comparatively small part of the world that is responsible for a large part of the world's emissions - have crossed a critical threshold in terms of climate change vulnerability. This news almost went unnoticed because it is nothing new to read negative news of this kind these days - be it climate change, plastic waste or species extinction.

But this news deserves special attention. After all, the boundary that has been crossed has only existed in this form for a short time - and with it the realization that it has been crossed.

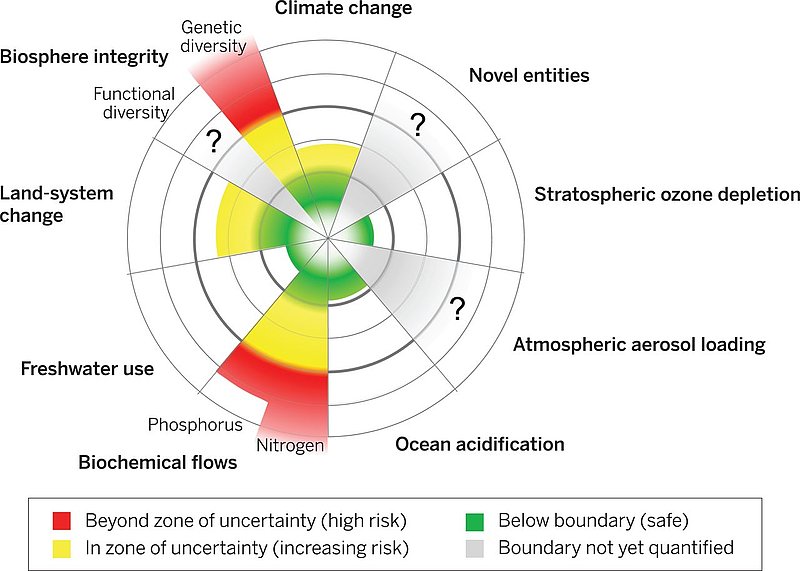

So what is it all about? A team of scientists from the Stockholm Resilience Center recently published a paper that, building on the globally known and appreciated concept of "planetary boundaries" (see graphic), takes a closer look at the relevance of chemical exposure. In doing so, they find that the impacts are much more far-reaching and complex than has long been perceived in the scientific debate and by the public. Following the concept of "Planetary Boundaries," the global ecosystem is ready to face acute danger if even one of the nine defined boundaries is exceeded.

While it has long been clear that, along with other challenges such as biodiversity, massive chemical pollution is a problem for ecosystems. But the extent to which it affects almost every part of our ecosystem, and how crucial it is to climate change accordingly, has long been unrecognized. Now scientists are concluding from their research that humanity has "left the safe zone." At the same time, they say, annual production and releases are increasing at a rate that even assessment and monitoring of these capacities cannot keep up. "We recommend urgent action to reduce the damage caused by exceeding the exposure limit," they write - aware of the fact that even in the best case scenario, the damage will continue for a long time.

Interestingly, when considering all possible releases based on chemical resources, the scientists single out plastic pollution as "of particular concern." Plastics would be different from more novel chemical releases, and would also affect the ecosystem in different ways - but the sheer volume makes them one of the main problems.

Possible solutions - especially for a risk that has long been so misunderstood - are not only complex, but also, as is so often the case, require a radical rethink. Unusually clearly, the scientists also name the social dimension for a successful and sustainable change. "A higher degree of circular economy in product supply chains, material and product design, design for recycling, and safe and sustainable chemicals," are not sufficient on their own, they say. "We must also address the problem of unequal distribution of resources and wealth that drives resource use and emissions (98) and hinders their effective regulation," they result.