How the Triple S Approach Can Help a Growing Number of Sustainability Scientists with Mental Health Issues

Mental health problems are common in science, too. Now, researchers are proposing an approach to reconciling the competing demands of science with those of self-care - to not only improve science, but also contribute to a healthier planet.

From the outside, the world of science seems exemplary, even almost problem-free. If there is anyone who knows how to solve problems and always acts rationally, it is scientists, isn't it? Many consider them to be conscientious, grounded people - that's the cliché.

What is often forgotten in the process: Scientists are subject to immense competitive pressure, they have to publish as much and as loudly as possible in order to be successful - taking time to be thorough is increasingly playing a subordinate role. Instead of reading and learning from others, there is more and more writing, writing, writing. Many researchers struggle to balance these demands of scientific rigor and excellence, societal impact and engagement, and self-care. Ultimately, they say, this makes scientists just as susceptible to mental health problems as people in other fields of endeavor, such as the private sector. So what can be done to ensure that those working on solutions to humanity's greatest challenges don't lose touch with themselves and the deeper meaning of their work?

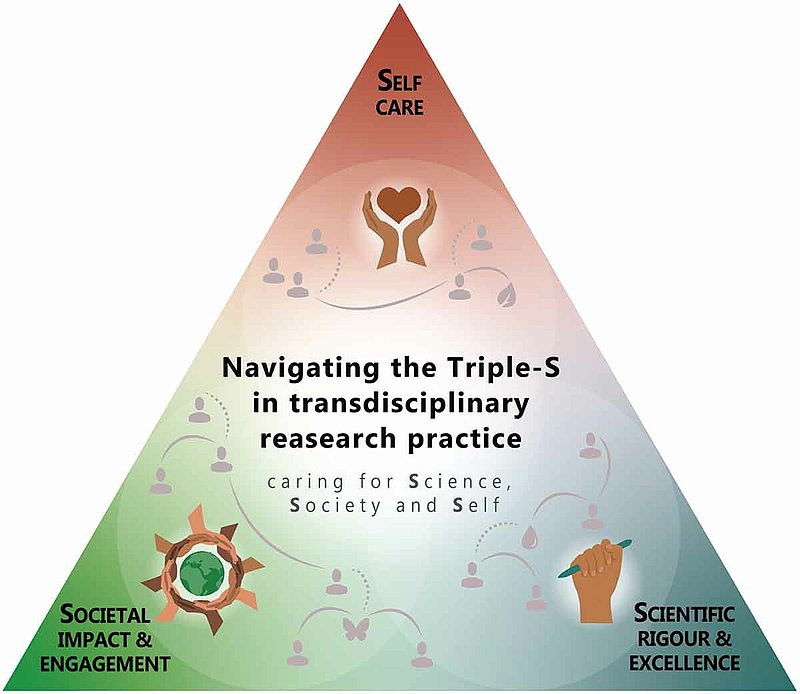

Admittedly, it would be presumptuous to answer such a fundamental question in a blog post - after all, the answer is not only complex, but also dependent on place and time. Nevertheless, scientists argue that there are some basic principles that can bring the broad field of science into harmony with society. Scientists from the Stockholm Resilince Centre have therefore now developed the so-called "triple S approach," which would allow the triad of science, society and self to be brought more to the fore again in practical research. This would have advantages not only in the first step for the researchers themselves, but in the second step for society as a whole. This heuristic should become part of existing transdisciplinary research that addresses the complex social-ecological challenges of sustainability to find solutions for all. However, it goes further. "The Triple S approach adds the often overlooked personal aspects of transdisciplinary research," the authors argue. "Current prevailing academic structures, cultures, and measures of success do not support a balanced and transdisciplinary environment, but create and exacerbate conflicts between these three aspects."

"Triple-S" stands for science, society and self. But the emphasis is on caring for the self because of the prevailing imbalance. "often the personal aspects of transdisciplinary research are overlooked - this is where we want to address them now," says lead author Sellberg. The challenge, she says, is to navigate this space in a caring and ethical manner. Because the three aspects of the Triple-S are so closely related, the challenge is not so much to keep the three "in balance" or to "compromise" between them, but to appropriately navigate and embody the relationships between these three components of the situation.

To that end, the researchers developed a theory of change, a step-by-step description of the activities and changes needed to bring transdisciplinary research into alignment with the Triple-S. "Caring is needed to build trust and establish collaborations with academic and non-academic stakeholders in transdisciplinary research environments. Transdisciplinary research ignores this in its practice even though it so often proclaims it in theory." According to the authors, caring postgraduate supervision of early career researchers can help them care for themselves on their journey in a disciplinary academic world and take care of the emotional and temporal difficulties. But, the authors emphasized, it's not just about taking care of ourselves - it's also about taking care of colleagues, especially those in the early stages of our careers, and the various academic and nonacademic communities in which we are involved.

Achieving this vision, he said, requires systemic change in academia. "We are now in a phase of preparing for change, planting the seeds for a thriving transdisciplinary research practice. An important first step toward this vision is the introduction of care and self-care as an equal dimension within transdisciplinary research."

"We hope this will create an academic environment in which transdisciplinary research practice can flourish and the next generation of researchers will be empowered, not burned out."